114

115

116

proportionately so large as to make generalizations impossible beyond a very gross level. Despite this limitation, certain patterns appear to have significance (i.e., 92% of Baptist/Fundamentalists would prohibit/censor certain topics, as opposed to 13%, or one, for the non-fundamentalists). In addition, certain formats are clearly matters of greater concern than others (i.e., comedies) revealed by frequencies.

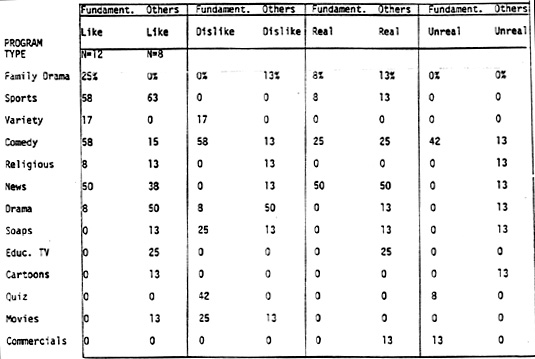

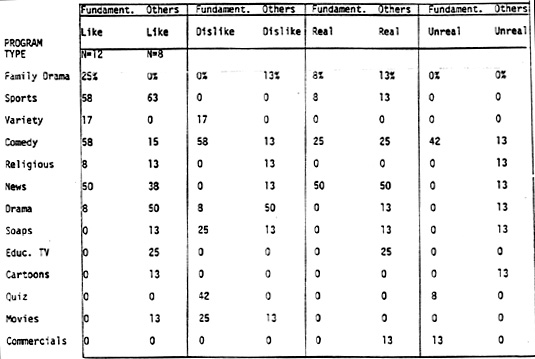

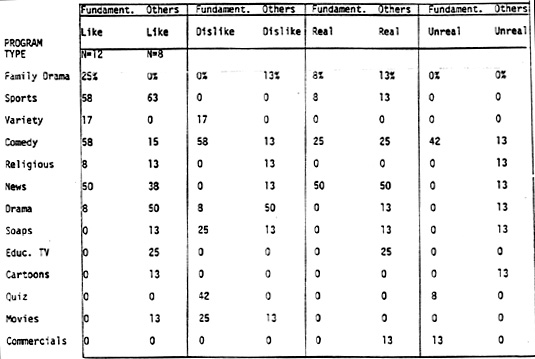

Findings (Fig.3A-B). The underlying objection to television programming offered by a number of Baptist/Fundamentalist respondents was a concern that television ought to portray, and therefore exemplify, a set of values congruent with the traditionalist image of the nuclear family. This image includes the belief that sexual activity is appropriate only within the formal marital union. Therefore, any depiction or suggestion of sexual activity occurring between other than a heterosexually married pair, is seen as inappropriate. In addition, the image of the family includes a certain status/role hierarchy in which parents are knowledgeable and authoritarian. The shows in which children are perceived as

117

"sassy," or parents as simpletons, are therefore likewise offensive. Living arrangements or households without the mother-father-child configuration were objectionable, both where this provides prurient comedic themes("Three's Company")as well as shows such as "Mork & Mindy," where the living arrangements are incidental to the subject of the comedy. Perhaps the recurrent concern with homosexuality is explained by reference to the presumed threat this behavior has on the family. In the extreme example, "MASH" was objectionable because Klinger dressed as a woman. In general, there was a feeling that the demographics of television were inaccurate in terms of family types, at least as perceived by Amarillians within their own milieu. The organizer of the protest felt that this was because the particular people who write these shows, who live in New York and Hollywood, are in fact living in immoral households andare consciously extending their values to the rest of the country. There may be some question here as to the effect of organized objection (the Evangelist, the National Federation of Decency, etc.) on bringing certain shows to the

118

attention of the public as objectionable, perhaps accounting for the greater overlap of mentioned shows among the fundamentalist group.

The most frequently objected to shows were the quiz shows which ask (sexually) embarrassing questions of either newlyweds or prospective dating couples. These were said to present a very poor picture of courtship and marriage. They also are on during the "Family Hour," when the networks are presumably catering to family audiences, making the perceived indecency more serious.

Preferred shows for the Baptists seem quite varied. Besides a general interest in news-magazine shows, which is apparently shared by the American public at large, there is very little overlap in preferential viewing habits (with the exception of Sports programming). Family drama did not seem to be significantly preferred, "Little House," receiving only two mentions, and "The Waltons," one. Despite the particular objections to particular comedies, comedy itself was, along with sports, the favored genre.

119

Sports was an interesting area of preference. No apparent connection was made between it and either sex or violence. Curiously, not a single informant raised objections to the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders sexual innuendoes (Dallas is the closest thing to Amarillo's home team).

The questionnaire replies do not support the Baptist claim to value realism as a rationale for objection to non-traditional families. Comedies were considered the most unreal of the genres among the Baptists, yet were preferred viewing. Clearly, comedy appears to be the most controversial format for televised information, and this finding suggests further study.

Among Non-Baptist/Fundamentalists, sexuality did not prove to be an overriding objection. In fact, it was only directly implicated by a single respondent, who was a Black Baptist (it may be that the distinctions revealed for perceptions of effects and preferences for prohibitions do not extend to program preference/dislikes--the Black Baptist and Catholic answers here look more like the Baptist

120

answers than the Jewish and Unitarian answers). More significant to this group was violence, but it was more in terms of its unreality than its objectionable effects per se that bore mention. While comedy was particularly popular with this group, there was also an interest in educational and factual programming ,as well as a high sports preference. However, there is not the overlap between preferred programming and unreality that there is for the Baptists, suggesting overall a somewhat different preference in terms of realism for television. There are some interesting responses, particularly from the Chicano Catholics regarding news: they (66%) either dislike or find unreal certain factual programming. The interviews revealed that the worldview presented as news contradicted in some ways the reality they themselves perceived. We take this to be worthy of further investigation.

In summary, while viewing preferences differ, though not significantly, between the two identified groups, attitudes about television differ significantly. In the previous section, this was revealed in terms of the perception of

121

effects. In terms of topics, it is revealed by 1) an apparent expectation for realism on the part of the Non-Baptist/Fundamentalist group, as opposed to the Baptist/Fundamentalist preference for a genre they identify as being unreal (comedy), and 2) the Baptist/Fundamentalist high response to topics that should be prohibited or censored compared to the relative absence of replies for all other groups.

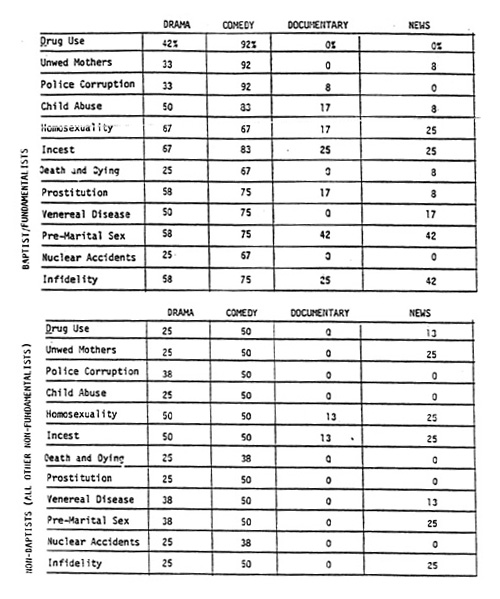

Percentage of Objections to Controversial Topics by Format (Fig.5)

The results of a written response to a topic/format question about "not good" programming produced the responses in this figure. Note that the replies for the non-Baptists obscure the interesting finding that both Jewish and Unitarian respondents felt that nothing was a priori "not good," and filled in no spaces. Hence, the figures are a result of replies from the Catholics and the Black Baptists, and if taken by themselves would be double the percentages listed. Given the small sample size, it should be noted that for these people preferences tend to be similar to the Baptist/Fundamentalists, suggesting that they be

122

123

more appropriately grouped together in terms of this variable.

The findings for sexually oriented programming tend to be consistent with the verbal replies. The identification of drug use and police corruption as similarly high scoring offensive topics is interesting. It tends to support the identification of the Baptist/Fundamentalists as Calvinistic in their moral outlook, and will be considered in the discussion section of this report.

Essentially, the scores of Fig.5 amplify the finding that comedy is the most controversial of formats, and the most likely to offend.

Preferred Responses to Objectionable Programming

The legal recourse to programming which is in violation of community standards for obscenity or for decency (these are legally distinct concepts) is to contact the Federal Communications Commission. While the FCC does not apparently like to act as a censor, they are empowered to act on abuses of the licensing of broadcast stations which are answerable to this

124

agency. Should the FCC consider a complaint valid, they may act to revoke the station's license and impose fines. In fact, this has never been done in the case of television broadcast, and only once in radio (along with another case which produced a ruling on indecency as a standard, but produced no action against the station). In any case, all complaints go into a file kept on each broadcast station and these complaints are considered at license renewal, every three years. Presumably, sufficient complaints may result in license revocation.

It is significant that not a single respondent, when asked, "What do you think the average person can do about programs they don't like?", identified the FCC as a possible avenue of redress. Instead, the following replies were offered:

| Turn it off | 10 |

| Write the station | 6 |

| Boycott the sponsor | 4 |

| Write the sponsor | 3 |

| Nothing | 3 |

| Write the network | 1 |

| Write the newspaper | 1 |

| Write a congressman | 1 |

125

It should be noted that the four "Boycott the Sponsor" replies were from respondents who had direct contact, either as participants or as newsletter recipients, with the National Federation of Decency, which advocates this form of protest.

"Turn it off" was suggested both as a single action and in conjunction with other action. Only three replies offered this as the sole recourse. While no generalities can be made on the basis of this respondent sample, this line of questioning formed a basis for a major section of the interviews with community leaders, and some correspondence is observable in relation to their constituencies.

Turning the set off (or switching the channel) was seen as the most appropriate response by the Station Manager:

"In a way, the home viewer has an advantage that the television station doesn't have in that, literally, we just have an on-off. They have other alternatives. They can watch the other channels or, of course, they can turn it off. I think that is significant because every time I'll mention to one of these groups, I'll say 'Don't watch', they say that that is a cop-out. Well, it's not. In '76, the television industry

126

perceived that viewers level dropped about 1%. A panic was experienced."

Indeed, the Evangelist felt that this attitude was a cop-out. One can't always be sure of what will be on. One cannot always monitor a child's viewing. The Pastor of the First Baptist Church apparently agreed, feeling that children are particularly susceptible. In fact, sexual innuendo, he felt, might be even more objectionable than overt sexuality, and one cannot simply turn off the set.

These opinions are in contrast to those expressed by the Catholic priest, the Black Baptist minister, and the Rabbi.

Interyiewer: "What would be the appropriate action an individual or group should take?"

Priest: "Turn off the TV. Perhaps you could boycott but that wouldn't be effective. ...I've never condemned a TV show (from the pulpit)." (He emphasized monitoring children's viewing by parents.) (Field notes)

Minister: "I think the appropriate stand would be to teach ... people on what to watch, .... and they should decide to watch it, then that's between the individual and his god. ... We're supposed to be mature people. I think the American public knows how far to go on

127

what they want to see or what they want not to see." (audio transcript)

Rabbi: "If I stood up in front of my congregation and said, 'You can't watch this TV show about incest because it's a sin,' they'd just laugh me off the pulpit." (He revealed that his three year old daughter regulated her own TV viewing, saying of violent programs, "it's not for kids". He also felt that the innuendos of, for example, "Three's Company," passed over her head and she enjoyed the program for its slapstick value.) (Field notes)

As to the solution of boycotting sponsors, the disapproval, with the exception of the Evangelist, was general. Her rationale was, "If they're going to continue to dish out this garbage, we're not going to buy it." Based on a perception of the writers/producers of the programs as themselves immoral, she felt that appealing to the fundamental economics of broadcasting was the proper solution.

Objections to the technique were based on a variety of factors. The minister of the First Baptist Church happened to advertise on the affected station. Hence, he was subject to and threatened with boycott. He was not pleased. It should be noted here that boycott is

128

a "people's" protest measure. Persons in power, the minister in question for example, have other channels of influence available to them and presumably favor such influence.

The Rabbi reported a fundamental objection to secondary boycotting, such as a sponsors boycott, and felt such measures were immoral and stifling to free enterprise. The Black minister felt, "Just as the individual is free, the sponsors of a particular show ought to be free to select where they want to sell their products". He drew an analogy to newspaper advertising, which is not boycotted if the news is bad. The Priest, in addition to his remarks above, drew a similar analogy.

It is difficult to say for certain whether the objections to the boycott as a method was based, in all cases, on the method itself, or the attitudes of church leaders to the persons who were organizing this particular boycott.

While none of the religious leaders suggested writing the station, network, or any direct contact (the questioning was not worded this way), the Station Manager revealed the he took "responsible" letters very seriously, and that they were capable of having an effect. He also revealed that he, as a matter of course,

129

was in contact with various religious leaders whom he could consult in any matters he felt might raise community objections.

The impressions one gets from the attitudes of individual persons or families is that the public is not in a particularly powerful position to affect what is broadcast into their homes. But in fact the interviews with the community leaders revealed that the community as a whole is not powerless. While the Station Manager denied ever having censored programming in response to direct pressure from citizens, he admitted to feeling a responsibility to satisfy community standards for broadcast. When asked who might best express these standards, he identified the Pastor of the First Baptist Church. The Human Services Director suggested that had both the Church of Christ and the First Baptist Church joined in the protest, the program would not have been aired. other informants suggested that such power was available to the church; they were suspicious of recurring problems of the particular station losing its network feed line at curious moments when controversial subjects were aired. In addition, programs appeared to be rescheduled or even replaced with no advance notice or explanation. In all such cases, the Station Manager

130

pointed to technical problems. But the community opinion is not necessarily consistent with this explanation.

In fact, the leaders of these powerful churches, particularly the Baptist Pastor, were said to characteristically avoid controversial issues. The Rabbi, who maintained a usually constructive rapport with the Pastor, remarked on his total unavailability for support of particular issues. The Black Baptist minister revealed the same situation.

The Evangelist who organized the local protest was a recent resident of the community, having come from the West Coast. A number of personal and political characteristics mitigated against her claim to be a spokesperson for the community as a whole. Her relationship with a number of church leaders appeared to be good, but she was apparently not a committed member of a single congregation, and as noted had alienated the powerful First Baptist Pastor. Her personal style, cosmetology, dress, and demeanor were perceived as somewhat foreign or worldly in respect to the local community. While this was not directly addressed by other church leaders, I was repeatedly asked if I had yet "seen" this woman. The emphasis on the visual in this question turned out to be significant. In addition, this

131

woman shared her mission with her husband who was Black. No other interracial marriages were observed in the community. Indeed, churches appeared to be de facto segregated by race. Finally, this woman's evangelical testimony, which formed the basis of her publications and presentations relied heavily on exposition of her pre-salvation sins. She had been a professional topless dancer, prostitute, and drug user. Her sins were therefore considerably more exotic than the community was used to. While this made her conversion and her testimony particularly powerful, it also raised questions for some. Her organizational affiliation for the purposes of the protest was through a religious agency, the National Federation for Decency. This agency operates in Tupelo, Mississippi, and while it has an (indeterminately) significant membership in Amarillo, it is not a local agency and none of the interviewed church leaders subscribe to its methods.

We suspect that the community does have potential, if not actual, power to affect programming decisions made by the Station Manager at the level of local church organizations, but that in the present case the spokesperson for the protest did not occupy the appropriate position in this structure to wield

132

sufficient influence to effect censorship.

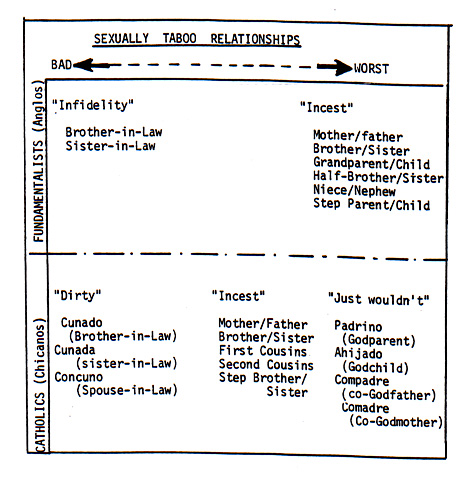

Unanticipated Finding; Cross-cultural Variation in Definition of Incest

All the people interviewed agreed on a core definition of incest, which included father-daughter, mother-son, and brother-sister sexual relationships. Other relationships considered incestuous fell along religious affiliation lines. The Fundamentalists were the most inclusive in what was considered incestuous: first cousin, second cousin, niece, nephew, step-parent, and son or daughter in-law. The Jews considered half brother, half sister, grandparent, and step-parent incestuous. The Catholics considered first cousin, second cousin, niece or nephew, and step-brother or step-sister as incestuous. The Unitarians considered no other relationships outside the core definition as incestuous. The inclusiveness or exclusiveness of definitions of incest correlates with the

133

inclusiveness of definitions of censorship and sexually offensive topics on television. The more far-reaching one's definition of sexually taboo kinship relationships, the far more far-reaching one's definition of sexually offensive non-kinship relationships on television.

An unanticipated finding was the relative "taboo-ness" of incest within the larger context of sexually taboo relationships; it was within this context that the differences between Anglos and Mexican Americans emerged. Viewing sexually taboo relationships along a continuum from bad to worst, incest is in the middle of the continuum for the Mexican-American Catholics and at the end of the continuum for the Fundamentalists. (Figure 7)

The Mexican-American Catholics said that sexual relationship among the godparent relations "just wouldn't happen" because it is sanctified by the Church. Several of the Fundamentalists did not know that a godparent was.

Even with a presumably universal topic such as incest, there is not complete agreement about its relative position in sexually taboo relationships. Censorship by one part of the

134

135

community could lead to insensitivity to another part of the community. If the Fundamentalists prohibit incest but allow topics about sex between godparents, this would be offensive to the Mexican-Americans in the community.

Conclusions

It proved very difficult to account for the impact of the sponsor boycott on the community or on the media institutions. No data were available, either of viewership (local sweeps were not made that week) or on the economy of Amarillo businessmen who were subject ot boycott pressure. One can say that the program was aired, some people watched it(although more probably watched the ballgame, as they said they would, and as their preferences indicated),and there was no perceptible business slump, nor did the First Baptist Church have to close its doors for lack of congregants the following Sunday. If we take the purpose of the boycott to be what was explicitly claimed as its goal, to force the hand of the local

136

station, then the boycott was a failure. However, it should be clear by now that this was not the entire purpose of the Evangelist's actions, and that the lack of data on the impact of the boycott probably worked in her favor. Variable claims could be made, and not disputed.

We should note that the sum of these local protests, nation-wide, was to give the National Federation of Decency and its founder, Rev. Donald Wildman, the appearance of clout for a brief period of time. Two of the three networks immediately directed research to the issue and claimed that such values and tactics as Wildman proposed had very few proponents as revealed by randomly sampled respondents nationwide. But despite this, Wildman was able to claim success in causing one of the largest national sponsors, Procter and Gamble, to withdraw advertising from certain shows. The discrepancy in the network findings and Wildman's effectiveness is suggestive. I believe it reveals a limitation of public opinion research design to the kinds of questions at stake here. It is not what people will say (over the phone, in the network surveys) to an "objective"

137

researcher in the specialized setting of an interview which matters. It is what the public posture of an individual or corporation needs to be given whatever image one wants to project in the social sphere. In Amarillo, this contrast was illustrated by the juxtaposition of the "Strip" and the churches and my belief that these two kinds of institutions served overlapping populations. The person who attended church and testified his faith publicly might also attend the "Crystal Pistol Saloon" and solicit strippers; but he would not be likely to testify to the latter. The social locus of an informant's response is the only tool that can be used to distinguish the kinds of opinions he might express in one or another setting. We can assume that for matters of public record and social expression, those which directly affect public personal and social policy, the values expressed in church would have considerably more significance. Proctor and Gamble executives, likewise, personally may not think that the concerns of the National Federation of Decency are particularly valid, and yet prefer to publicly support them to convey a public image. The question is therefore not one of

138

privately held opinions but publicly expressed values. How one accounts for one is quite different from how one accounts for the other.

If the purpose of the exploratory study was to determine what kinds of questions are raised in the public forum about television's effects, the Amarillo example suggests that they are questions of values, as illustrated by the responses reported in this chapter. Values are a curious analytic problem, but as they are claimed to be components of the cultural system, it seems worthwhile to account for these values by speculation regarding the cultural models which might underlie them.

In the search for cultural models that underlie social behavior, it has been noted that the statistical aggregation may obfuscate rather than reveal the salient features. In kinship studies, for instance, marriage rules may be strictly observed by only a minority of given society. Yet social anthropologists often insist that a consistent logic may be discovered which can account for the cultural expectations which govern marriage, and that such logics or rules are important not only as interpretive devices, but

139

matter greatly to the members of the society as well. Statistical aggregation would in many cases misrepresent these rules. Other techniques are used to elicit them, notably inquiring of informants as to what the proper conduct should be, and observing what happens when the rule is breached. Through such techniques, a very small number of responses can be generalized to broad advantage. An analogy to linguistics helps explain this approach. Because language is rule governed, it takes very few speakers, properly interviewed, to construct the grammar and vocabulary- of a language. In fact, one accomplishment of early anthropological linguistics was to reconstruct dying languages from a single last survivor of a given tribe. In this conclusion, I will construct models of belief systems observed in the Amarillo community as they pertain to television. While this is accomplished through a very small number of replies, the limitations of these models, and their tentativeness as conclusions is more related to the brief time of observation than the number of participants in the study.

We recognized two major models operating

140

in this community. The predominant one, the Baptist/fundamentalist/evangelical model is apparently similar in particulars to Calvinist theological principles as applied not only to media, but to sexuality, family organization and child-rearing. This is important because most of the concern over television's effects appear to be based on fears about children's impressionability, regardless of the source of concern. A correlary universal concern seems to be that the impression television makes on children may intrude on the family structure, i.e., that it usurps the prerogatives of parents. We know there is some diversity of childrearing models across the population. We suggest here a correlation between these models and models of television's effects. In order to know what parents fear television is doing to their children, one must first know what parents prefer to be done to (or for) their children. Several spheres of influence are therefore required to account for the perception of television's effects. We have attempted to organize these influences to generate models which will account for and predict the data retrieved in

141

Amarillo.

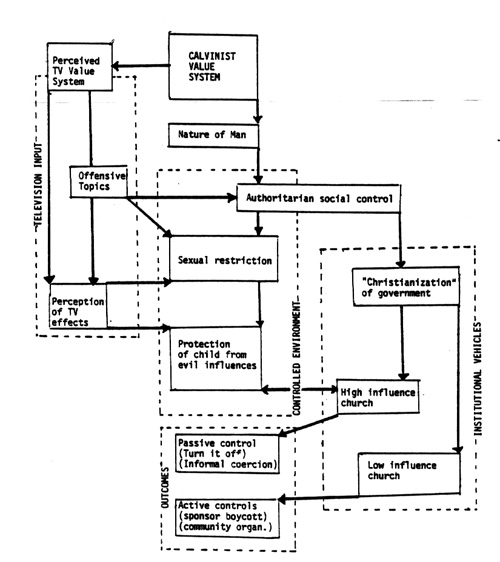

Figure 8 organizes the responses of the subjects associated with the Baptist/fundamentalist/evangelical churches to account for the relationships between variables and to predict preferences in respect to the control of broadcast television. Three spheres of significance are identified in this essentially cybernetic treatment of the pertinent systems: TV input, conception of the environment, and institutional vehicles available for mediating between the input and the environment. Ideology is seen as the entry point into the total system, and the outcome (for our present purposes) is reckoned in terms of censorship preferences.

The diagram provides us with the following observations:

1) There is a direct relationship between the value system, the conception of man, sexual restriction, and the protection of the child from evil influence through control of the environment, by "proper" authority.

2) Offensive topics are offensive in that they question authoritarian social control, or they threaten sexual restriction.

3) TV is perceived as threatening sexual restriction and causing children to be vulnerable to evil influence as primary

142

143

effects of viewing.

4) Authoritarian social control implies a governmental system which acts to enforce controls, and thereby assist in protection of the child as well as enforcing sexual restrictions.

5. While these features are common to Calvinist thinking, the outcome in terms of attitudes about censorship depends upon the individuals' institutional affiliation. Where the affiliated church has power within the secular community, that power is perceived as adequate and proper to maintain the controlled environment. where the church is not influential, individual or community action is perceived as necessary in the form of media watchdog organizations and activities such as sponsor boycotts.

6) By implication, less influential churches are not seen as adequate protectors of children from environmental evil.

Therefore, given 1) the particular value system, and 2) the institutional affiliation, the actions of the subjects becomes predictable.

In essence, we are observing two routes of influence on the television input system. The pastor of a powerful church will have achieved his influence by management of his circle of associations over the years. He is not likely to support a community protest, particularly of sponsors, since these sponsors are likely to be

144

influential businessmen who may figure prominently in his power base. That they sell products advertised during a certain show may even be beyond their control (i.e., in the case of local franchises of nationally distributed products). Moreover, the sponsoring group of the protest, the NFD is not a local, but a national group headquartered elsewhere, while his power base is local. By taking cautious public stands on controversial issues, and applying pressure informally in private, an influential pastor may work to the same ends as the NFD. His goals, however, are more pragmatic, and more concerned with local influence which is more realizable than is attempting change at the national, network level. He is not likely to trade-off his successful local influence for unrealizable national goals.

The Evangelist, however, has no such local power base. But she does not regard the power structure of the religious community as adequately serving local needs. While she claimed that the powerful churches did not join the protest because of intra-church competitiveness ("They

145

didn't start it, so they won't join.") , she also questioned both the actual influence and the personal motives of the church leaders. In any case, had they been doing their job, she, "just a local housewife," wouldn't have to be doing it for them. We conclude that the differences between Baptist or Fundamentalist attitudes about television are therefore more a function of how individuals perceive their status in relation to the community organization structure than in respect to ideological differences.

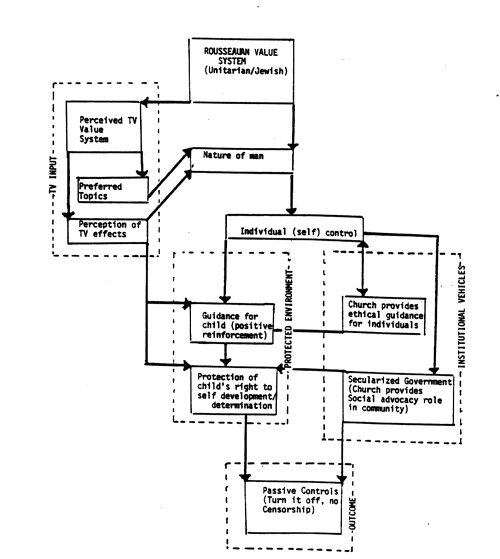

Rousseauan Value System (Jewish/Unitarian)

Ideological differences are more apparent in comparing Fig.8 to the following figure, Fig.9, which identifies the same system within the context of a Rousseauan value system. For the philosopher Rousseau, the child exemplified the perfect, natural being; that is, the child's nature is quintessentially good. The child also has the potential for development by exploration of his environment. The parents act as a guide, and may, to some extent, provide a protected environment boundary within which experimentation may take place. The goal is to create a self-reliant

146

147

individual, answerable to his own conscience. The function of the state is to attend to the business of Caesar, regulating personal behavior as minimally as possible. when the state intrudes for these people, it is more likely to provide opportunity than to limit it. The function of organized religion differs somewhat for Jews and Unitarians, the exemplars of this system in our sample. However, in both cases, the church may advise the government, but it is more likely to act in reaction to restrictions than to impose them. The Black Baptist minister also exemplified this value system, but the case is less clear among his parishioners. (We suspect racial identity to have impact on the issues, but are not adequately equipped to describe this impact here.)

The Rousseauan System, then, will always produce a non-censorship outcome. There are, however, possible responses to dissatisfaction with programming. These are the people we would most expect to invest in cable, VTR's, or other systems which extend rather than limit the range of programming. These are also the people who are

148

most likely to report that they will substitute TV watching with reading (F=88%). Notice also that this is the group with the highest expectations that television be realistic, and express concern that TV may effect man's self-perception, or social perception (see Figs. 3 & 4). TV is also seen as having the capacity to inform and therefore provide guidance for children. Hence, the arrows which connect the TV input to the environmental realm are very different for this group and tend to be bilinear rather than causal (double arrow). Topics correlate with nature of man, and effects additionally are not seen to influence the environment in any remarkably negative way. In short, these people see TV as another feature of the environment, not particularly dangerous, as the environment itself is not seen as threatening. The church, as noted above, may advise government, but in terms of protecting not restricting individual actions.

A similar diagrammatic treatment of the Chicano Catholic community might also be developed, and further work in this is recommended. However, the small sample and the problems of distinguishing

149

between Roman Catholic and Latin American Catholic values is beyond our present scope and sample. For this group, a particular issue emerged worth some attention here. We know that value systems are an expression of cultural background and that different systems reckon values differently. While this is observable at the model level for the preceding groups, the specific difference revealed by the research in the reckoning of disallowed sexual relationships which bears directly on the questions of homogeneous community standards. In the particular issue of incest, the Rousseauans reckoned only a few relationships as prohibited due to incest restrictions, essentially sibling relationships and parent-child relationships. The Baptist/Fundamentalists generally treated all familial relationships as incestuous, consanguineous as well as affinal. The Chicano Catholics were more selective, however, considering incestuous feelings between mother and son, for example, understandable and discussible, although a forbidden action. In-law (affinal relationships) were "dirty," but not, properly speaking, incestuous. However, a purely social relationship,

150

that pertaining to god-child/god-parent, was the most unthinkable and forbidden. The policy implications of these sub-cultural differences are significant. If incestuous subjects for media presentation were defined as a violation of community standards, the definition of which relationships would be incestuous would still not be resolved. If the prevailing standard were the view held by the majority, relationships which the Chicanos felt were an expression of "normal, but unacceptable feelings," could not be explored, while relationships which are reckoned as forbidden, as between god-parents and children, might be permitted. While the particular example might seem in some ways trivial, it may signal differences in the interpretation of other human relationships and other topics where such disparities might also occur.

A number of predictions may be tentatively advanced from these models projected into the social future of Amarillo. First, it seems unlikely that the television issue will persist as a significant focus for the theological community. The circumstantial alignment of the

151

powerful churches against the boycott, and the antagonism to the Evangelist seem to confine to defeat the specific effort, and will probably generalize to a growing disconcern with the issue itself. Second, the similarity of underlying values identified for institutionally diverse groups implies that other alliances may be formed around other issues where Calvinists might combine, and where Baptists, Fundamentalists and other Evangelical groups could unify to exercise political clout (indeed, these seem to have been true in the past as well). Finally, although the Evangelist failed at her avowed objective of forcing the media's hand, she did manage to assemble a para-institutional constituency which could operate as a force in the community under some circumstances. If her national exposure continues to develop, the ability of the local television media to deny her access might be overcome and her ministry could be legitimized. A caveat, however, is noted in terms of her interracial marriage which seems of some concern to some of the citizens of Amarillo. Should a national base develop, other communities might

152

appear as more conducive home

bases for her work.

Proceed to Chapter

3