50

CHAPTER TWO

EXPLORATORY PROJECT: AMARILLO, TEXAS, OCTOBER, 1979

Naturalistic Description

The bias of ethnographic models is that particular items of behavior or belief are explained adequately only by reference to their relationship to other items within a holistic model of the community in which they occur. With this in mind, the following discussion is designed to locate this study within a larger picture of the Amarillo community as a whole.

Amarillo, Texas, is a medium sized city of about 150,000 souls. Located in the center of a geometrically pristine rectangle jutting out of the northern border of Texas known as the Panhandle, it straddles two counties, themselves both perfect

51

rectangles. "Flat as a pancake" is the local's favorite way of putting it.

There appears to be no reason why Amarillo should be situated in this particular location, rather than a bit to the left. or right. Descending into the airport, the city suddenly appears to the west, an irregular grid punctuated by a few large modern towers. The city seems to end, as abruptly as it begins, at some invisible boundary beyond which there is only the endless flatness of the High Plains.

People here tend to stay put, to seek out their amusements within this grid of development. The nearest city is Lubbock, about a hundred miles away, and differs from Amarillo only in minor respects, heightened by the characteristic competition of such sister cities, as though they were competing football teams from adjacent neighborhoods. For excitement, and anonymity, you need to go as far as Oklahoma City, or Dallas, several hundred miles east, or even Albuquerque, further to the west.

In the 19th century, this was ranchland, part of the largest ranch in all Texas, the XIT.

52

Secured from the native Americans only in the second part of that century, the XIT was deeded in payment for the costs of the state capitol building in Austin in the 1870's. Scots played a central role in this transaction, and were among the early settlers of the Panhandle, as were other Anglo and some European stocks. The city itself developed as an accident of geometry, transportation, and Central Place Theory. The intersection of several of thegreat cross-country railroads occurred at the point where the city now stands. For years, the highest structure in town was the old B&O tower. Subsequently, the automobile and the tractor-trailer contributed to the city's growth because Route 66, that legendary thoroughfare, crossed the northern section of the city. The sparse grazing lands were intersected, and trucking and distribution activities such as feedlotting, emerged to compliment the meager ranching economy. As aviation developed, Amarillo maintained its status as a transportation center; the first cross-country commercial flight stopped here. The Air Force established a major airbase. Route 66 became the focal point for transients moving

53

through the city by truck, by rail, or by air. Among the services the area provided were honky-tonks: alcohol, music, and erotica. And so, the highway became known as "the Strip". Even when the airbase was phased out in the late 60's, the Strip remained. Topless bars, street walkers and some pornographic media are still available here and presumably supply a local, as well as transient clientele.

Yet even on the Strip there are churches. Churches are as visible in Amarillo as bars are in some cities, dotting apparently every intersection or so throughout the area. There are 225 recognized churches in the city, nearly one for every seven hundred fifty persons. The church occupies a central position in the social institutions of this city. While there are other organizations of importance, PTA, Rotary, Optimists for example, none wield the power of the churches. In fact, it might be said that such secular organizations are used as ecumenical, interfaith resources, where the Rabbi and the Minister meet casually over lunch and where important issues that face political leaders can be discussed with

54

religious leaders. It appears that church membership is not just high in this community; it is nearly universal. Wielding personal power or ambition here without utilizing the extensive friendship and political networks of the churches would be unthinkable. In fact, there is a prestige and power hierarchy among the churches: one is well advised to match one's social and personal ambitions to the correct church.

For people in Amarillo, issues of morality and sin, family values and religion were active struggles taking time and resources in daily life. For the community is not yet so large as to create the sense of social impotence characteristic of large urban areas. As the city grows toward such a size, community leaders are feverishly working to build that firm foundation which will provide moral defense for their children from the evils of urban living.

How does Amarillo manage this disparity between the honky-tonks of the Strip and the conservative religious values of the residential community? It might be said that Amarillo was built on communications channels, in the form of

55

railways, roadways and airways that connected this city to the rest of the world. Traffic, of both persons and ideas across these great linear conduits could be regulated so that the city experienced a certain removal from the pressures and changes of the rest of the world. Even today, the city has the odd feel of a town of ten or perhaps even twenty years ago, or perhaps a contemporary city that continued to grow as if the 60's and 70's never happened. Unemployment is said to be almost nonexistent. Energy problems seem at most a foreign plot, since oil wells still pump only a stone's throw away. Even though it appears that extensive feedlotting may have depleted the grazing lands' water supplies to a point which may be catastrophic within the coming few years, no one seems overly alarmed. Conservation was not an issue here in 1979.

Nor do the races mix. Churches and social life are racially segregated as if by oversight more than exclusion or design. Yet there is design here, of a particularly spatial kind. The linearity of the communications conduits allows for the qeoqraphic separation of the solid citizens

56

from the transients, of the Black from the White or Chicano, of the saints from the sinners. Although older churches, built before the 1940's, may be located on what is now the "wrong" side of town, none of the parishioners are likely to live near these old churches. In extending our sample to minority cultures, telephone exchanges were reliable indicators of class and ethnicity. The transients, meanwhile, are relegated to the Strip, where presumably solid citizens never go. But they do, apparently, sometimes. Because there is an old fashioned kind of sinning that can take place here, as sin requires a heightened moral code to give it proper weight.

Within the last generation the careful moral balance, spatially regulated, has been disturbed by a new form of communication. Television signals are not easily regulated, entering or exiting via routes easily controlled by railroad switches, toll booths, exit ramps or airport gates. Television has intruded on this community through an unguarded gate so that New York discos and West Coast "living arrangements" appear nightly in living rooms all over town.

57

People one would never even have on the front porch now come to dinner nightly at the turn of the dial. Here, on this flat grid carved out of the High Plains, there are some who are concerned that the great battle between the devils and the angels that has been so long balanced for this community is about to rage once more. But this time, the devils are more insidious, more dangerous. These aren't houses of ill repute, easily zoned or torn down, or fallen ladies whose face paint is as bright as any other sign on the Strip. The new devils arrive as electronic transmissions, activated particles, invisible, intangible, and perhaps uncontrollable. It was this battle that we were to witness.

The research team, myself and two female interviewers, came to Amarillo on the basis of a newspaper story which reported that a local housewife had led a pray-in at the offices of the Amarillo CBS affiliate station. Prior notice of a made-for-TV movie about a boxer who has a love affair with his mother had provoked what appeared to be a spontaneous community outburst. Because our research contract involved the study of television effects on families, this seemed like a

58

reasonable opportunity to survey the issue.

Preliminary inquiries to community leaders revealed that the situation was somewhat more complex than was anticipated. The local housewife was, in fact, an Evangelist with a growing national reputation. She was an interesting and charismatic figure, to the community as well as to the researchers. Her powerful testimony (available in books and audio tapes titled, "The Other Woman") revealed her to have been a peerless sinner prior to her experience of the Word. Her exploits as a sinner were considered in light of- her salvation to offer evidence of God's concern for even the most hopeless. She had been an exotic dancer whose performance with snakes landed her in the pages of Newsweek. She abused drugs, and turned "tricks" to pay for an expensive lifestyle which she shared with her boyfriend, a Black jazz musician. Both were saved, married, and came to Amarillo to continue their ministry. They were, as far as could be determined, the only interracial couple in the area, although it should be noted that never was this mentioned by any informant.

59

The background of the protest, which emerged through interviews with community leadersr was of a struggle for power within an existing intra-church system. The dominant denomination in Amarillo is Baptist, accounting for 55% of the population and commanding the dominant place in the political structure. The traditional leader of these Baptist churches is the First Baptist, founded some ninety years ago. The Pastor is acknowledged to occupy a place of singular prominence in the community as a whole, commanding as he does the largest church membership and apparently the biggest budget. Pentecostals are the next most numerous, and the combined membership in all churches which could be described as evangelical or fundamentalist is over 70% of the local population. Church of Christ, Mormons and Methodists are also well represented, Catholics considerably less so; and Unitarians, Quakers, Eastern Orthodox, Jews and Christian Scientists each maintain a single congregation. Yet, some of these smaller congregations may still be politically significant. Although there are only three Episcopal churches, their members may have

60

high social and economic status, as is traditionally associated with this denomination.

Church leaders are expected by their congregations to take responsibility for representing congregations' interests in public policy questions that may relate to morality, such as drinking licenses, gambling laws and pornography issues. To accomplish this, church leaders maintain an active social network with other such leaders and local politicos. Secular organizations may act as settings, neutral territories where these leaders meet and where decisions affecting the community can be discussed over lunch or dinner. In this way, the church wields influence informally as well as formally. Should conflict on issues arise, as it did on the issue of drinking at the new civic center, the churches have proved capable of replacing secular government with co-religionists.

This structure represents a fairly traditional hierarchical influence system in which the individual or family has only indirect appeal to public decision-making through church relationships. In the case of the Evangelist, a

61

low-influence leader, the protest was serving to appeal directly to a "grass-roots" constituency. She developed the media issue through the National Federation of Decency, a national organization, and united a few less powerful local leaders behind her. Together, they staged dramatic media-events to attempt to attract a sufficiently large pressure group to accomplish what more powerful leaders might have been able to do over coffee with the Station Manager at a Rotary meeting. In a number of ways, she directly and indirectly threatened the existing leadership structure through these tactics.

The ensuing events, the progress of the protest, and of the boycott, and the outcomes in terms of public opinion cannot be described or appreciated without reference to the situation outlined above. Similar protests were raised in a number of other cities across the country where the NFD is active. But none it appears were so dramatically staged as in Amarillo. Part of this may be due to the particular controversial characteristics of the Evangelist, but part certainly had to do with the implied challenge to

62

the community structure.

Exploratory Interviews:

Community Leaders

The two weeks the research team spent in Amarillo prior to the broadcast of the targeted program were structured to avail ourselves of the maximum possible data in the short time available. The usual random sample of respondents' attitudes would have required more assumptions about the community than our limited prior knowledge could support. Rather than attempt to construct a model of the community by a statistical analysis of responses, we relied on the public structures of the community itself to provide a selective sample of response. First we contacted the parties directly involved in the dispute, the Evangelist/housewife and the Station Manager. We also made advance calls to social service professionals in the community and asked them about the issue and who seemed actively involved. Certain names repeatedly emerged, most of them religious leaders. As we conducted interviews with

63

these leaders, we entertained suggestions for additional community leader who might help us understand the community and the situation. Whenever a community leader represented a constituency, we also solicited names of individual constituents who we might interview for a small "snow balled" sample.

The community leader interviews were open-ended and loosely structured. We shared with them the purpose of our research by identifying and probing the basic questions:

1) What kinds of programming are objectionable;

2) What effects they think objectionable programming might have;

3) What action should be taken, and by whom, in response to objectionable programming.

These interviews were quite extensive. Our expectation that people would be particularly willing to talk about matters of current concern to them was rewarded by extended conversations, in some cases more than three hours long. Interviews

64

were conducted in settings chosen by the respondents: their offices or over lunch in most cases. The purpose of these settings was to make the interviews as comfortable and casual as possible. But an important unanticipated advantage was that in most of these settings, the respondent was not isolated from his usual social or professional responsibilities. Calls were made to and visitors stopped by professional offices, and luncheon meetings often involved some table hopping, since we were interviewing well-known figures. This provided additional data revealing relationships among various people in the community.

As we continued to interview, we began to develop an image of the community as well as a general model of what was happening in this particular issue. As the interviews evolved, these hypothetical models became an additional and increasingly important area of questioning. After fielding the primary research questions, we would offer our own observations and interpretations about what was happening. The respondent was then free to agree or disagree or refine the

65

observations and thereby provide us with evidence for the reformulation of our image of the communiy. In our later interviews, it was our model of the community, shared with respondents, which elicited the most extensive, and in some cases the most provocative data. Respondents wanted to know where we got certain ideas. In cases where particular person's opinions were matters of public record, we would reveal sources. In other cases we would explain that the confidentiality we were extending in the present interview also protected previous sources. It was not unusual in these cases for a respondent to guess sources, and both accurate and inaccurate guesses were informative. What emerged from this technique, beside the image of the community, was a growing appreciation of the relationships between community leaders, as well as attitudes that different segments of the community held about each other. In particular, the channels of communication available to and used by different people or segments of the community were revealed.

A problem with this technique arose because we ran a recurring risk of acting as

66

facilitaters to communication between parties who would not or did not normally participate in direct dialogue. The temptation to provoke by doing exactly this was great, given the data it would have produced. The value of cross-checking information between respondents had to be carefully weighed against the possibility of altering discontinuities characteristic of the communication flow between the parties involved.

Family Questionnaire Interviews

A questionnaire instrument was designed to identify the attitudes about television in the broader community to supplement the interviews with community leaders. The instrument was applied to twenty families, an admittedly small number for survey research. But the intention was not to sample the opinions of the community as a whole through a representative random sample but to refine the models of values and interpretations of media and media effects which were revealed by community leaders. We also sought to determine the

67

consistency of attitudes of the leaders with the attitudes of their constituents. This would determine to what extent the community leaders could be considered accurate spokesmen for larger groups. Presumably, leadership is based not only on the relationships between powerful individuals, but on the relationship of each leader to the people he represents. Had we discovered major inconsistencies between what the community leaders objected to about television and what offended their constituents, this inconsistency would have to be accounted for or the research design would come into question.

The value of this technique, interviewing persons who speak for the community and checking their responses against a limited sample of their constituents, is twofold: 1) We observe that policy determinations at the local level are rarely made by democratic referendum; rather they are made by people in power. Therefore, analysis of the responses of policy-makers in the community helps us understand the natural course of events in a local setting; 2) Comparing the responses of the leaders with their constituents, we can identify

68

the power base of the leadership and if generalizations to the larger community are in order, the responses can be mapped on to the community in terms of the institutional and associational demographics which are available. If we find that in a particular locale, this disenfranchises a significant population, we can perform some random sampling of the non-aligned to provide a more complete picture. But the weight we give to the responses of non-aligned individuals or the less powerful social groups is informed by our model of the community structure. This is a very different approach from the random sample survey, which assumes an equivalency of response that disregards the practical effects of social organization on decision forming and making communities.

Initial Findings

Media Access and Media Usage

Television represented the most powerful

69

communication channel for the standpoint of all parties. Community power of individuals and groups was consistent with their access to television. The Pastor of the major Baptist church was repeatedly identified by respondents as the most powerful spokesman for the community. His church bought several hours of air time every Sunday to broadcast church services, which included a major public address in the form of a sermon. The channel on which this was aired happened to be the same channel on which the targeted movie was to be shown. Because the Pastor had an on-going business relationship with the Station Manager, his power was enhanced economically, symbolically and practically in terms of media access.

The Evangelist, however, had no readily available broadcast forum. In order to develop one, she had to create newsworthy events which would generate enough attention to provide some time on the local news programs. Clearly, one of the functions of the pray-in was to provide this access to the television medium. Another avenue she was able to develop was an appearance on a nationally syndicated religious interview show, the

70

"PTL (Praise the Lord) Club". She was slotted for two hours of testimony on this program during our fieldwork. The first hour was to offer her personal testimony and the second was to discuss the issues surrounding the objections to media (im)morality. What actually happened was most curious to us, as well as to the parties involved. The "PTL Club" was aired in this market at 6AM and therefore probably had limited effect on the general public. Even so, the program on which the Evangelist appeared was not broadcast as scheduled. The explanation offered by the Station Manager was that there was a mix-up in distribution; they didn't receive the proper tape. The show was aired the following day, but only the first hour was shown. It couldn't be determined whether the second hour was supposed to have been shown the next day or not. In any case, only half the testimony was actually aired, and that at an unanticipated time. There is no way to assess responsibility for this. we can only remark on the curiousness of the situation and identify the potential control the Station Manager has over information whether or not it was intentionally

71

exercised in this case. Predictably, different members of the community assigned responsibility differently in explaining the events.

A clear antagonism between the Station Manager and the Evangelist could be observed. But from a business perspective, the Evangelist could be said to be providing a service for the station. Advance men for both movies and television know that even negative publicity often attracts additional viewers, and it might seem that the Station Manager would actually benefit in terms of ratings from the controversy. In response to this line of questioning, the Station Manager agreed that the Evangelist was probably working at cross purposes in this case. The antagonism probably was the result of political rather than economic concerns. In fact, there were no ratings made of the viewing audience that particular week, and no way to evaluate the penetration of the movie or the effect on audience size of the protest. This originally seemed a handicap to our investigation. But this very lack of ratings may have highlighted the political issues which could be foregrounded without the usual economic stakes that ratings

72

imply.

To appreciate the political situation, we need to include the Baptist Pastor in the cast of characters. In our initial phone call, he volunteered his antagonism toward the Evangelist's campaign. The centerpiece of the protest was a boycott of all advertisers who bought commercial time on the station which showed the movie. It was believed that by approaching the advertisers, the most effective pressure might be brought to bear on the station as well as the network. This technique was designed by the National Federation of Decency of Tupelo, Mississippi, which maintains a nationwide media watchdog and pressure group network. The Evangelist was acting as the area spokesperson. The principle behind a sponsor boycott is based on a reasonable reading of the economics of television. But as we shall see, it is based on very poor community sociology in the Amarillo example, and perhaps everywhere. We have noted the interdependence of status, influence and Church affiliation in the Amarillo community. Presumably the local sponsors of broadcast programming are wealthy, and to some degree

73

influential members of the community. We can assume, therefore, that they will maintain close ties with the important churches. These sponsors are not likely to be sympathetic to a religiously based boycott of their products, or appreciate the pressure the Evangelist sought to exert over them. Such sponsors may be policy makers within the influential churches, and the divisiveness which boycott techniques could produce within the local theological community and within each church might present dangers to the entire political structures of these institutions. But as it happened, the most influential Baptist church itself was a sponsor of the local station, since it purchased air time. As a result, the church itself was threatened with boycott. The ensuing events provided an excellent demonstration of the combined effects of the church/media power structure and ensured the failure of the boycott.

Community Leader Interviews

Baptist Pastor. The interview with the Pastor was the first we conducted. The number of

73

gates one had to pass through, the secretaries and officials that regulated access to this man both in phone calls and in person, were impressive evidence of his status. The interview was conducted in the Pastor's study, a classically appointed, book-lined room of the sort that one associates with the British gentry. It was the briefest of the interviews partly because of the Pastor's schedule, and partly because as the first formulation of the situation, we had little in the way of a hypothetical image of the situation to discuss. The attitudes the Pastor expressed about television would later be discovered to be identical in most particulars to the Evangelist's. The significant differences emerged only with respect to the appropriate means of influence to be used to alter programming. The Pastor did not approve of the boycott, although probing failed to reveal precisely why or what other means of influence might be applied. He was polite in his remarks about the Evangelist, although he was explicit in his disapproval of her attempts to force his own hand by including his church in the list of those subject to boycott. He did note that the

74

Evangelist was new to the community and he did not feel she represented any major constituency. He asked quite pointedly whether we had seen her yet. The emphasis on the visual in this question was repeated in other interviews, sufficiently pronounced as to make us wonder about its significance.

Station Manager. The interview with the Station Manager was extended and casual, moving from a meeting in his office to lunch at an impressive private club to further discussion back at his office. From the club's vantage point atop the highest building in the city, the conversation naturally addressed general characteristics of the area, the overall situation with local media, as well as particulars about the boycott controversy. The Station Manager suggested that he had an on-going, respectful relationship with the Pastor, whom he held in high regard. He believed that if a single person were to speak for the Amarillo community as a whole, it should be the Pastor. The values expressed by the Pastor were regarded as normative for the community, although the Station

75

Manager's own values did not conform with these in all particulars, he felt.

The Station Manager indicated in his conversation that he did not regard himself as a powerful person in the community. He did not, for example, represent any constituency. Nor was he a public figure, in the sense of being visible in the community or appearing as a spokesperson. He characterized himself as something of a functionary and a businessman, in a mediating position between the directives from the network and the expectations of the community. There were relatively few decisions he said he could make from such a vantage point. He considered the availability of several channels and an on/off switch as according greater control to the viewer than he himself had. He said he had never succumbed to community pressure to censor or withhold any particular program. He did pay attention to "responsible" letters regarding programs and policy. And of course he was sensitive to ratings.

Despite the humbleness of the Station Manager's self-characterization, the interview

76

shuttled between locations which bespoke obvious prestige. The modesty of the gentleman's demeanour could not obscure the very real power we observed him to have subsequently. Others in the community did regard him as powerful. A number of people questioned whether broadcasts had in fact been censored by recourse to tactics which could place responsibility on technical and distribution failures.

Evangelist. The interview with the Evangelist was the most productive and the most demanding of the entire series. The other communitv leaders had been interviewed in their offices and private clubs which provided ample contextual support for their prestige. But this interview was conducted in a public restaurant during a busy lunch hour. Other community leaders were able to evidence their position by framing the interview within an architecture of power. Conversely, the Evangelist had to construct this evidence from commonly available materials. These included several associates, specifically her husband and a woman who presided over a local Right

77

to Life group, as well as others lunching in the same restaurant. By accident or design, several people happened to be there who came over during our conversation to offer advice and consent. It was well into the luncheon before the actual interview began, and it was the Evangelist, not the interviewer, who took the initiative. throughout the interview, there was a covert struggle for control between the two. The Evangelist had been a professional interviewer and proved quite sophisticated in these skills. It was tempting to allow her total responsibility for structuring the dialogue, except that the topics and anecdotes she offered were essentially similar to those already available through her own presentations and publications.

After the purpose of the research was explained and the research questions had been addressed, we proceeded to share our emerging image of the community and ask some specific questions about the strategy she had employed. We particularly wanted to know the basis for the letter she had sent to the Pastor threatening

78

boycott of his church and whether she had anticipated his adverse public reaction. At this point, the interview became provocative, because the line of questioning, no matter how carefully worded, seemed to touch significant nerves of the issue. While the Pastor had been indirect in his personal evaluation of the Evangelist, she was quite blunt in her assessment of him. She took the established churches, and the Pastor particularly, to task for failing to act on the issues at hand. She pointed out that if they had been doing their jobs, she would not have to be organizing the protest. Had the protest been initiated by the church, it would have been singularly effective. But since they did not originate it, it was left for other people outside of positions of authority to organize. The churches presumably resented this usurpation of their prerogatives and therefore would not cooperate. Lacking the traditional power base, the participants in the protest felt themselves vulnerable to attack, and this might produce some defensiveness, she admitted.

The objections to television she expressed, and the values violated by network

79

programming were consistent with those expressed by the Pastor, although they were considerably more detailed and were very useful in constructing the model of the Baptist/Fundamentalist value system (p. ) which was supported by the later community survey. A methodological aspect of the interview is significant, however, and merits discussion.

The Evangelist was particularly concerned with the values held by the interviewer and his predispositions to the issues under discussion. While interviewer bias is generally excluded from empirical research, we felt that in the present case the Evangelist was entitled to ask these questions. After all, we were not surveying an issue which had been created by the researcher, but we were intruding on active issues of importance to the community. The Evangelist had much at stake in this controversy, and how we portrayed persons and events could have direct bearing on outcomes for her. Other interviewees did not attempt to interview the interviewer, partly because their positions in the community were secure and partly because they may have been less skillful at this kind of role-reversal.

80

The interviewer, in response to direct questioning and after due consideration, identified himself as belonging to a no-protestant religion. We hoped that this would provide for a more explicit presentation of the Evangelist's views since no assumptions could be made about shared religious values. At the same time, we suggested a shared purpose: the pursuit of knowledge regarding the effects mass media has on families' self-determination in raising their children.

The identity of the interviewer certainly had direct effects on the tone of the interview and the nature of the information revealed. it may also have had a bearing on the Evangelist's later refusal to cooperate further. But this model of collaboration in the elicitation of information, as contrasted with the one-way flow of data in laboratory settings, is characteristic of the ethnographic procedure. It reminds us of an important fact of naturalistic observation of spontaneously generated events: the interviewer and the fact of research do indeed affect events. Where all parties agree to ignore these effects, the illusion of dispassionate observations can be

81

maintained. But the potential for the researcher to become an actor in the events he describes is real, and he cannot fault any respondent for correctly sensing that.

The Evangelist did not share the researcher's valuation of scientific objectivity, since it stems from an epistemology essentially different from her own. Her attempts to structure the interview on the basis of her principles and not ours can be regarded as a sophisticated assessment of her prerogatives as a research subject. In this awkward and sometimes provocative exchange, a great deal of valuable data were produced, and we were reminded of the complexity of the observer's role in scientific inquiry.

Model of Community/Mass Media Interface

We can abstract from these interviews, the additional interviews with other community leaders and our brief membership in the Amarillo media audience a kind of ecology of media for this locale. Each medium has a particular status

82

attached to it, and presumably a certain influence, along with particular possibilities of effects and constraints on information peculiar to each. Community leaders, and those who wish to become community spokespersons, have variable access to the different media, and this access appears to be in direct proportion to their own status in relationship to the status of the medium. Even though there were substantive issues regarding the events we had come to study (media values), they are best presented subsequent to this discussion of the general meanings accorded the media itself in this community.

Television

Of the mass media (radio, television, and the press), television clearly occupies the highest status, and the access for input is limited to high status community members. Access to the airways was restricted to:

1 ) Those who purchase air time, either as commercial sponsors, or who buy time directly, as in the case of church broadcasts.

2) Local personalities who might

83

be called on as experts on local issues on talk programs or as commentators to news events.

3) Persons directly involved as actors in local newsworthy events.

4) In exceptional cases, local figures may be of national interest and have access to network or syndicated programs locally aired.

The Pastor fulfills the first three criteria. The Evangelist, by contrast, has tenuous access at points three and four. Note that the only requirement for access at point one is money (which is to some extent equatable with power). But points two and three are based on subjective evaluations: what is newsworthy, and who is expert. Therefore, the local community can determine whether it will provide access at these points. Point four, national prominence, not only provides access through imported programs, but would normally entitle a person to access at points two and three. It is very hard to deny the newsworthiness or the expertise of a local figure who is nationally known. But this did in fact happen to some extent with the Evangelist. She was

84

given very little attention by local media as a personality, and mainly in connection with the conspicuous event of the pray-in. It would have been reasonable to assign her status as an expert and call on her for commentarv and as an interview subject. This did not happen. meanwhile, during the entire period of controversy, the Pastor was delivering two sermons every Sunday via the airways. But he at no time mentioned the issues or the persons in the controversy. His silence on these issues may in fact have been a contextual message, confirming his power and influence by publicly ignoring an issue in which the community knew he was involved.

Newspapers

The press' portrayal of non-fiction events is perhaps no less subjective than television's in the sense that events become news because the media decides to pay attention to them. But newspapers legitimize far more events and their coverage is more extensive than in a TV broadcast. In general, the same points of access apply to the press as to the newspapers and their formats are

85

somewhat similar. The status attached to newspaper access appears to be less significant than that attached to TV. In cities of this size, nearly everyone in the middle class and above will be newsworthy at some time. This may be due partly to the number of items needed to fill any given edition. But the lesser status may also be due to the lesser penetration of the newspaper.

The Evangelist was given far more play in the press than on television. Several first-page news stories appeared, accompanied by large pictures. The Evangelist was interviewed, extensively quoted and, in general, the treatment of her was sympathetic. In fact, the Evangelist claimed she no longer spoke directly to the Station Manager or the Pastor, that they were much more likely to communicate through the mediation of the press. Despite the attention given to the action-oriented aspects of the protest (such a the pray-in), as the time for the target broadcast approached there was little attention given to the boycott, even in the press. This may be in part because there were no visible events to report. The possibility of doing features, interviews or

86

follow-ups was not developed. The initial exposure the press provided, therefore, was limited in subsequent impact and the degree to which the Evangelist's validation of status could be accomplished by this somewhat less effective medium.

Radio

The radio's impact was not assessible. We know that shortly before the research team arrived, a call-in program had been devoted to the issues, and the Evangelist claimed that the support of her cause had been extensive. The radio announcer involved in the program disagreed. But no transcript was made available for an independent judgment. Perhaps a characteristic of radio is that the broad spectrum and lack of clear-cut prime time allows for radio broadcasts to be variously reported and interpreted, since it is assumed that not many people will be listening. The power of the medium to validate status in such a situation would naturally be limited. The Pastor's Sunday sermon, it should be mentioned, was also carried on the radio, extending the penetration of his

87

message.

Direct Communications

Besides the media, there were various other communications channels utilized by the community that bore on these events: letters, telephone calls and direct address (both formal public speaking and casual discourse). The letter seems to have had particular importance in creating the events. The avowed source of the Pastor's antagonism was his receipt of a letter from the Evangelist. The letter, according to him, was of a threatening nature, forcing the Evangelist's issue by demanding support of the boycott. He was given the choice of withdrawing his sponsorship of the station or being subject ot boycott himself. Any consideration of the Pastor's political and social position in the community would reveal that this is an untenable demand. But what seems to have particularly bothered the Pastor was that the letter appeared to be a form letter. as such, he was being treated without the deference due his status and with no regard for his delicate position.

88

The Pastor's response to the letter would seem so predictable to anyone familiar with the socio-political realities of life in this community that the possibility that the letter was sent by oversight occurred to us. We asked the Evangelist if this was so, or if she had anticipated (and thereby implicitly provoked) this response. of all the questions we asked in Amarillo, this produced the most heated reply. the Evangelist felt that the Pastor had misinterpreted the letter. But she proceeded to question further both the motives and the authority of the pastor. She felt that his failure to do his job, that is to protect the community from immoral influences, was the reason that she had to create the protest. As a result, she brought into question the authority of the Pastor and the appropriateness of his status. This helped us to understand the political issues being negotiated in the context of the boycott. What we could not determine was whether these issues stemmed from the boycott itself or preceded it. In any case, the letter form played a major role.

Face-to-face contact is the other mode of

89

communication significant to the controversy. Two types were observed: the social dialogue and the public speech. We can only guess at the extent to which the social dialogue was used by participants, since we could not be privvy to such occasions. The private nature of these interactions gives them much of their value. We did discover the primary configuration that obtained between the three major actors. The Pastor and the Station Manager often maintained such a personal dialogue, and the Station Manager had, in fact, discussed the protest with the Pastor at a Rotary Club luncheon and perhaps at several other times. The Evangelist, on the other hand, had no access to such dialogue with participants. In order to communicate with either party, she claimed to use the press as an intermediary. The implications of this configuration were that the Pastor and the Station Manager would be able to use their dialogue to consolidate their positions, and any specific questions which either had could be directly resolved. Miscommunication between the Evangelist and either of these two parties would be difficult to resolve, however, depending on the press to

90

mediate disputes. As a result, certain issues, such as those created by the letter from the Evangelist to the Pastor might have been defused if a social discourse were available. Since it was not, and since the parties did not work to establish this kind of interaction (although it is not possible to say if the Evangelist ever attempted to do so), what may have been a misunderstanding became a central political issue in the protest.

The public speech is important particularly to the Pastor, since he maintains an ongoing public forum, with a large audience: his weekly sermons. The Pastor, we may observe, is most skillful and most at home in this face-to-face communication and his media broadcast is, in fact, an extension of his sermon through the television medium. In this manner, he can be said to maintain face-to-face contact with a large number of local citizens. It is interesting that the sermon during the service we attended remarked on this fact. Although the topic was fund-raising and therefore somewhat dry, he noted repeatedly how many persons who did not directly participate in the

91

congregation nevertheless willed money or contributed to his church because they maintained contact through television. The message of the sermon, then, is of the Pastor's influence in the community beyond even the walls of his sizable church.

The Evangelist also used the public speaking setting, although she lacked an established forum like the Pastor's. She spoke at

local churches, and often appeared at various local and nationally based groups to offer her "testimony". The pray-in itself was a public speaking event for her, but the content of her speech was more extensively covered by the press, and barely by the broadcast medium. We should also mention that the Evangelist had published a book which apparently had a significant readership among evangelical Christians, and a cassette tape of her testimony is available commercially as well. Generally speaking, however, we can characterize the Evangelist as a print-communicator, in that most of her access to the community was in the form of the written word, either directly (books, letters) or indirectly, as reported by the

92

newspaper, for example. The Pastor, however, was a speech-communicator, able to communicate directly his own spoken words through his sermon, which were televised as well, and through face-to-face dialogues. Characteristics of print vs. speech may have some bearing on the observed situation.

Comparison of Media

"The moving finger writes," we all know, and one is committed to one's prose in a manner that is quite different from speech. The written word commits statements to exact recall. In the case of mass distribution, the books and the press, the entire community has exactly the same data on which to base opinions. Speech, by contrast, is a more flexible communication resource. A speaker's audience may be less critical of inconsistencies in a spoken discourse, particularly if the speaker is frequently available and the speeches verbose, as sermons tend to be. A number of community leaders noticed that the Pastor tended to avoid the press, particularly on controversial issues, so no bibliography of his opinions would constrain the maneuvering presumably necessary to maintain a significant political role. The flexibility of

93

face-to-face messages in private interactions is immense for political activities, and the inclusion of the Pastor in a network of face-to-face relationships with influential community persons obviously was a value denied the Evangelist.

It appears that limiting the Evangelist to print media not only limited her effectiveness in general, but ignored her particular performance style and skills. Prior to her conversion to fundamentalist evangelism, she had been a performer. She was a visually dramatic person and a fluent speaker herself. She appeared quite comfortable and effective on the television interview program, when it was aired. In fact, in our interview with her, her cosmetology and style reminded one immediately of her theatrical background. She had hosted her own radio interview show in Hawaii before moving to Amarillo. The repeated question, "Have you seen her," turned out to have a double significance. Her appearance was indeed somewhat more stylish and worldly than was common in Amarillo, at least among the churches we are discussing. A community member suggested to us that if she were to join the large established

94

church, the Pastor might be advised to first talk to her and see if she might tone down her appearance. It is particularly significant, then, that we were in Amarillo an entire week before she was visible. This woman, who was so well qroomed for theatrical and broadcast settings was denied these settings by the power structure of the community. There appeared to be some implicit consensus that outside of these settings, she was or could be made to appear stylistically inappropriate. Not only was the legitimating medium or broadcast television withheld, but the community attempted to establish expectations in the researcher for her invalidation in the casual settings which were available.

Questionnaire: The Community Values

The value distinctions between the various fundamentalist/evangelical sects and churches proved insignificant. The distinctions between the Pastor and the Evangelist, therefore, must be construed as wholly a political dispute about the means to similar ends as well as

95

legitimacy of particular persons' authority. The Baptist/Fundamentalist community as a whole, clearly felt that it maintained legitimate authority in the Amarillo area, and that certain television topics and programs represented a violation of their values. In such cases, a significant majority would forbid or in some ways censor programming aired locally.

Baptist/Fundamentalist Values

The values the Baptist/Fundamentalists maintained for television were consistent with those they expressed in other circumstances as well. The basic premise is that there is a normative, sanctioned family structure and that deviation from this structure or from the behaviors approved for the personnel in this kind of family represent immoral behavior. The family structure is a hierarchical male-dominated one. The father occupies the central, authoritarian position; the mother is subservient to him. The only sexual conduct appropriate under any circumstances, and in any social or intimate setting is between these two persons. The children of this union are expected to accept the authority of the parents and behave

96

in accordance with the values the father determines (based on appropriate rules of conduct, consistent with biblical values).

The Baptist/Fundamentalists' objections to television are therefore predictable as applications of this simple family configuration. Any sexual contact outside of the marriage bond is immoral. Portrayals of male-female relationships in which the female is authoritative are disapproved. Kids who are "sassy" to their parents are acting indecently. Homosexuality, by combining sexual behavior outside of marriage and inversion of authority and responsibility roles for men is doubly obscene. Innuendo and contextual inferences are as immoral as graphic portrayals. Hence non-traditional living arrangements, such as "Threes Company," are offensive, but so is "Mork and Mindy," even though there is no sexual conduct implied by these characters' living arrangements.

It is not necessary that the intent of a television program be licentious. The very presentation of unapproved behaviors or relationships is considered the equivalent of sanctioning that behavior. Questions about

97

distinctions between formats, i.e., fiction/non-fiction contexts revealed that minimum distinctions are made, nor does the sensitivity of a portrayal have much importance for this group. (As contrasted with the Non-Baptist/Fundamentalists). Topics which are unacceptable are unacceptable in any case. The child is considered especially vulnerable, and it is not desirable to put unnecessary or immoral ideas into his/her head. Children are conceived as pre-moral. The parent has an obligation to exercise his authority by excluding from the child's environment depictions of experiences which may be harmful. The model of television communication and effects underlying these attitudes is simply stated: Portrayal leads to imitation. Children can't make moral judgments except by recourse to moral adults in authority relationships to them. Therefore, portrayal = sanction.

The importance of the authority figure in protecting children may be central to understanding this value system. A perplexing problem we encountered was that the Evangelist's testimony,

98

both on television and in her book, contains many of the same contents as were objected to generally for television and specifically for the target movie. Before she was saved, the Evangelist had encountered most of the serious sins available to a contemporary woman. In the final chapters, she undergoes conversion through direct experience of the "Word". But until this point, the book is frankly racy. Why isn't it subject to the same objections the community has to television and other media? It is precisely because the woman's salvation earns her a position of authority as a member of the moral community. In light of this, we can understand the very high stakes involved in the Evangelist's dispute with the Pastor. For if access to the legitimizing media is withheld, and the Evangelist's authority is not validated, her testimony itself subtly comes into question. This is precisely what was implied by some of her antagonists, both among the leaders and the community itself. The consistency between the Baptist/Fundamentalist leaders and their constituency cannot be fortuitous circumstance of the site or an artifact of the research procedure.

99

It is revealed to be a necessity of the prevailing value system. The implied attack that the Pastor and the Evangelist made on each other's authority is in fact the central issue. Because in this system, the person who speaks for the people is, in fact, acting for the public in many significant areas of social life.

Television itself cannot be a proper authority, although it can legitimize local authority. The sources of network television programming are outside of the community, and outside of the religious value system. Standard commercial television's imported signals will therefore always be suspect, unless acknowledged religious leaders were to take control of the networks. Television programming will continue to provide an ongoing issue in such communities as we are describing. In order to provide anything other than programming which conforms to the normative values outlined above, a religious legitimizing authority must be present. Since programming is not likely to conform to these requirements, it may be depended upon to provide the backdrop for community political negotiations of similar sorts

100

in other settings.

Non-Baptist/Fundamentalist Groups

Despite across the board agreements that the Baptist/Fundamentalist value system as articulated by the Pastor of the major church characterizes Amarillo as a whole, other groups with other values co-exist with Baptist/Fundamentalists. In a controversy which affects media availability for the entire community, these minority values must be taken into account. Even if Amarillo is predominantly Baptist, the unique quality of the community as a whole can only be appreciated with respect to the relationships between the various groups in the context of the strong Baptist influence.

Definitive statistics on religious demography are not available for the area, but repeatedly a 55% figure was offered for the Baptist population. In addition to Baptists, other churches which are classified as fundamentalists include Pentecostals, Church of God, Bible Church and some non-denominationals. Our interviews and questionnaires provided a basis for tentatively classing the Church of Christ and the Church of

101

Latter Day Saints along with the fundamentalists, since replies from these sources were essentially identical to the Baptists. Political and social distinctions that may characterize these churches presumably do not extend to significant value differences in their congregants' opinions about the surveyed issues. Therefore the 55% figure for the Baptist membership is considerably amplified when we include these additional denominations in the Baptist/Fundamentalist category.

What kinds of denominations are left? We did meet a few heathens, and we assume that there is a proportion of the population that isn't church affiliated at all. But even these few non-believers seemed to maintain at least casual church affiliation. A visit to the Unitarian Services gave us the odd feeling that this was a church for people who didn't believe in church, that even non-believers in Amarillo required some parareligious affiliation. There was a particularly poignant moment in the Unitarian service when a woman asked the congregation what body of dogma she could offer her children who were

102

subject to such great peer pressure by the fundamentalists at the public high school. The question was not directly answered. Another Unitarian woman had to leave an interview to attend her daughter's Baptism. Despite her strong personal convictions, this woman could not provide her daughter with sufficiently secure grounding in Unitarian principles to resist the enormous pressure exerted even at the adolescent level.

Clearly, groups like Jews, Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Episcopals, Unitarian and Quakers, all of whom maintain churches in Amarillo, also maintain a different set of values from the fundamentalists. The case with Methodists, Presbyterians and Christian Disciples of Christ is somewhat less clear, and our sample did not include any of the above. But without making precise claims for demographic accuracy, it is fair to say that Amarillo includes a significant majority community of Baptist/Fundamentalists with a small, but still significant minority of persons holding other beliefs and values.

Unanticipated Finding

An interesting qualification emerged with

102

respect to a racial variable. The interview with a Black Baptist Pastor revealed an entirely different set of values and beliefs from the White Baptist Pastor. He placed a high value on independent thought and did not believe the media should conform to church or even Christian values, let alone be required or pressured to. He felt that he was often in an adversary relationship to the powerful white churches (as did other minority church leaders) and that the protection of his congregations' prerogatives required an active, libertarian interpretation of first amendment rights. The denomination itself didn't prove Ito be the indicator of values in this case. A member of his congregation, however, offered replies more consistent with the White Baptist replies. The apparent contradiction here is informative. The Pastor claimed that he could not speak for all his congregants, as he did not present an authoritarian figure nor did he feel he should. This kind of discrepancy between leaders and congregants appears to be an indicator of non-fundamentalist values. Similar discrepancies were observed in the Chicano Catholic community and the Jewish community,

103

particularly. This may be a basis for considering the ethnic/racial variable in the construction of the model of community and church influence.

Even in cases where particular replies of particular members of the minority congregation were consistent with the Baptist fundamentalist answers, the general inconsistency between answers by members of the same congregation and with their leaders is distinguished from the high consistency of replies in the Baptist/Fundamentalist community. The Baptist/Fundamentalist community shared very similar values, but revealed differences based on political grounds (who in the community was a proper spokesperson). The minority groups, on the other hand, differed somewhat in values, but expressed very similar feelings that regulating media to make it conform to a single value system was not advisable. In short, they placed a high value on political diversity, rather than disputing which authorities should occupy the role of spokesman.

Questionnaire Results

104

Perceived Effects of Television

Findings. Among the most significant questionnaire data were the responses to the questions: "Do you think TV has any effect on the way people act in real life?" and "Do you think TV has any effect on the way children behave?" With few exceptions, responses to the two adjacent questions overlapped, so they are collapsed in the analysis (if separate replies are desired in future surveys, the order in which the questions are asked should be reversed).

We began to sense that the replies were of four types. First, there were what we might call direct effect responses. These tended to relate presumably empirically observed effects of TV watching on people's moods, activity and daily routine, and tended to be content non-specific, i.e., "My child seems agitated after watching a lot" or "TV takes up a lot time". (C.F., Winn, 1978). These replies were infrequent, (F=15%) and did not pattern in relationship to any other variables. The indirect effects responses were more interesting in that they appeared to correlate

105

with the religious-political variable.

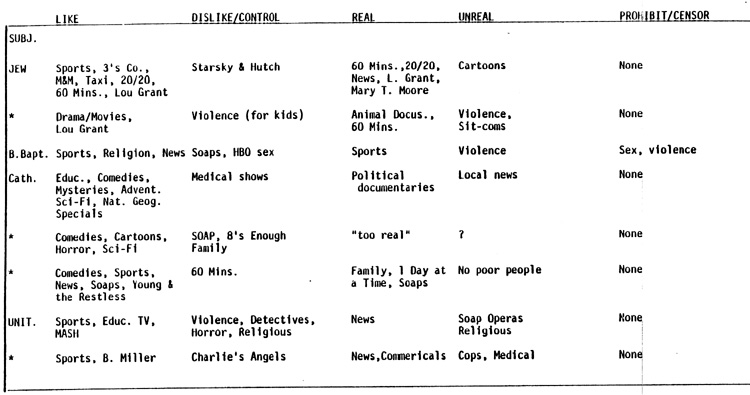

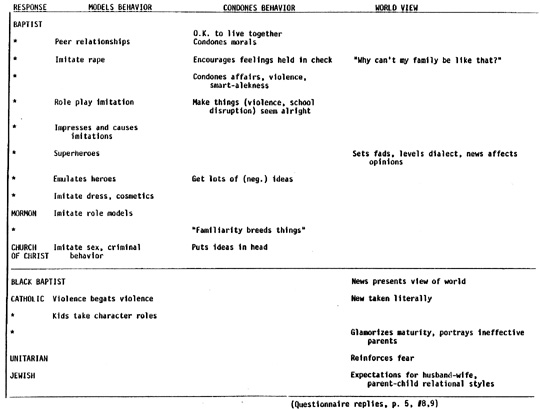

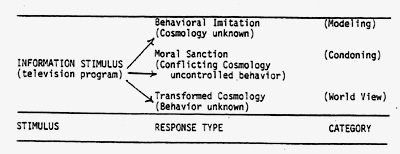

Analysis of FIG.1, "Perceived indirect effects of television," is on the one hand quite simple in that, of the twelve Baptist/Fundamentalist respondents, eight replied in terms of television's effects on condoning certain behaviors (67%), as opposed to no replies of this sort from the other, non-Baptist respondents. On the other hand, only two Baptist/Fundamentalists perceived television as affecting world view (17%), as opposed to 83% of the other group who perceived indirect effects, or 63% of the total group (two respondents perceived no such effects) .

Variables. The replies are grouped into three categories: Models Behavior, Condones Behavior and Affects World View. While there is some overlap in response types (and many respondents gave more than one type reply), the tripartite distinction attempts to respect emic categories, and refers to somewhat different concerns.

Models Behavior pertains to (usually) direct imitation of behaviors presented on the

106

107

screen, in direct stimulus response pattern. Included here are the frequent responses revealing that children pretend to be superheroes by imitating particular mannerisms of such characters as "The Hulk". Included here also are responses that suggest children, teenagers, or adults will model behavior, most often sexual, after behavior presented on television. The models underlying this response might be said to be behaviorist and/or stimulus-response.

Condones Behaviors pertains to a concern that the presentation of information is equivalent to the sanctioning of that information. While the distinction between this category and modeling behavior may not appear discrete in the reduced replies in the accompanying diagram, the questionnaire replies and the audio recordings make the distinction more dramatic. The concern here is not simply of imitation or direct response; it is of permission. Some respondents model of mind/behavior requiring that immoral or animal impulses be controlled (presumably by authority figures). The concern with condoning effects of TV is two-fold: 1) it

108

puts negative impulses into the mind or the subconscious, and 2) it somehow weakens the will's (superego's?) ability to control these impulses. The underlying models here are not behavioristic. Rather, they share some features of the Freudian model, may involve cognitive restructuring and we suspect ultimately pertain to a Calvinistic view of man, morality, and child-rearing which will be discussed below. This is not surprising in that these responses were limited to members of fundamentalist Protestant sects.

Affects World View pertains to responses which spoke not about individual action or behavior directly, but about the manipulation of cosmology. These included both concerns with the pseudo-realism of TV news being taken literally, as well as the presentation of ideal relational styles. Implied, and in some cases stated, in this response is that the individual's attempt to experientially validate this cosmology may produce a variety of unsatisfactory responses, i.e., dissatisfaction with one's own family, unreasonable fear of violence, etc. This is very much the sort of concern Dr. Gerbner has about TV's effects.

109-110

Note that this response does not predict behavior at all. Rather it defines a reality construct in which the individual's choices of action may be limited but remain ultimately free. This corresponds to cosmological and social-structural models of behavior and to the transformational model of psychological treatment.

Discussion. Part of the apparent overlap between categories of response may be due to the observation that the categories themselves form a continuum in respect to a polarity between behavior and cosmology. Condoning behavior occupies a middle position in which the effect of information is on behavior within an a priori construct. The categories may be conceptualized as follows:

In short, we find that the data suggest that variable perceptions of effects of television on viewers can be correlated with variations of more basic systems of belief about the nature of the mind, man, and presumably the conception of the parent/child relationship as it pertains to perceived effects on children. It is not surprising, then, that the sectarian variable built

111

into the sampling procedure revealed differences in perceived effects of television along religious affiliation lines.

By and large, modeling was perceived to be an effect by all groups (though there were no such responses from Unitarians, Jews, or the Black Baptist, the analysis of the rest of their interviews suggests a larger sample would provide more of such responses). However, the concern with Condoning Behavior was limited to members of the fundamentalist Protestant sects (seven of eleven respondents). For non-fundamentalists, the power of television to affect world view was most significant (five out of six). Only two Baptists mentioned such effects, and one of these was atypical: the only non-parent, the youngest respondent, and himself a radio news broadcaster. In the following section we will attempt to correlate the underlying belief systems with these differences of response.

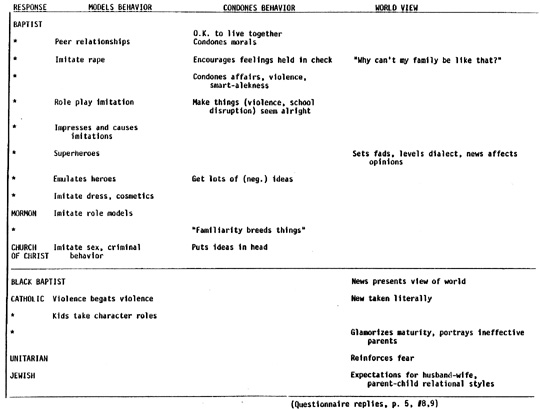

Topic/Format Preferences and Prohibitions and Perception of Realism

Coding method. It appears that viewers conceptualize television content in terms of three

112

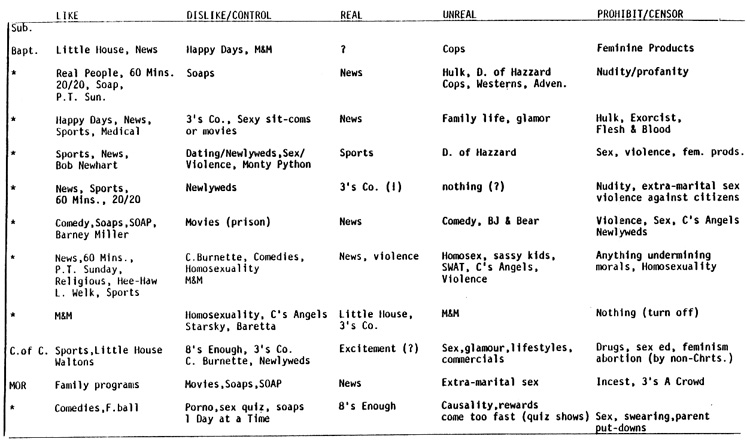

categories: topics, formats, and specific programs. Preferences for viewing may be expressed in any or all of these terms. To some extent, it might be said that the researcher built this assumption into the questionnaire a priori, but in fact, the more open-ended questioning in the early part of the interview confirmed this assumption giving credence to the more structured questions, for example, on the written section that followed the interview. Oral and written responses are analyzed separately (oral, Fig.3A-B; written, Fig.4), and do not contradict each other.

Preferences, objections, and prohibitions may then be expressed in any of the three categories, making coding somewhat difficult. Fig.3A-B respects this difficulty by reporting direct responses to questionnaire categories. Fig.4 collapsed the distinction between particular programs and formats to produce a frequency of responses for program types (i.e., the reply "Happy Days" and the reply "comedies" are both counted as COMEDY). A word of caution is in order: the sample size in the present pilot study is relatively small so that standard deviation is

113

114